British Mahjong

This is the last in a mini-series of articles about different mahjong rules. When me and Donnie set out to write our series, we were conscious that we could only ever scratch the surface. Mahjong didn’t start at a single point with a single organization steering it’s growth, rather it was a collection of concepts and spoken conventions passed from village to town to city, being molded and changed by each participant so that each version looked quite different from the other once it had reached its destination.

We picked up rulesets we felt were big enough to have reached the ears of most players (with the notable and perhaps unforgivable exception of Zung Jung). This last article will cover a ruleset perhaps not known to the majority of players—British Mahjong.

“First Brexit and now the British have their own mahjong?!” I hear you cry. It’s true! Proving our nation’s tendency for non-conforming, we have our own set of mahjong rules which has taken its own unique route on its travel to land on our humble shores.

It is not without a healthy player base of its own, although you may have to look a little closer to find them. Many players seem to be affiliated with the University of the Third Age (U3A), and there are are uncountable house groups. They don’t tend to advertise their activities as heavily, but this might be a carryover from it starting as a parlor game in the mists of time.

They do have a ruleset, although not one that seems to be heavily policed. I have myself found three books with slightly different terminology and variations in its game play. I decided to plump for the British Mahjong Association’s volume published by Bloomsbury under the “Know the Game” series for my initial research as this seemed to be the most authoritative.

I’ll admit, when I first tried to read and grasp the British version of the game, I was entirely lost. It didn’t seem to make any sense. Chiis are basically worthless, as are “dirty” hands (hands that are made up of multiple suits). But that was because I was misunderstanding a vital conceptual difference between British and most other forms of mahjong; your hand is scored even when you haven’t called mahjong.

I only realized this once I sat down with a group of British players in my local library. They have a passion for their game in the same way I have passion for riichi, making it easy to find a common ground and get caught up in the stories over the fence from their garden (coincidentally, they have a “garden” yaku!).

When a player calls “Mahjong” in British rules, that hand is scored and also ALL hands that are tempai are also scored. This creates a situation very similar to MCR where you are always live and in the game. There is also a tendency toward calling for pons because of the high value they bestow. It’s a very different attitude to the tiles compared with riichi, but not an unhappy one. Tempai, value, and efficiency are the key tenants.

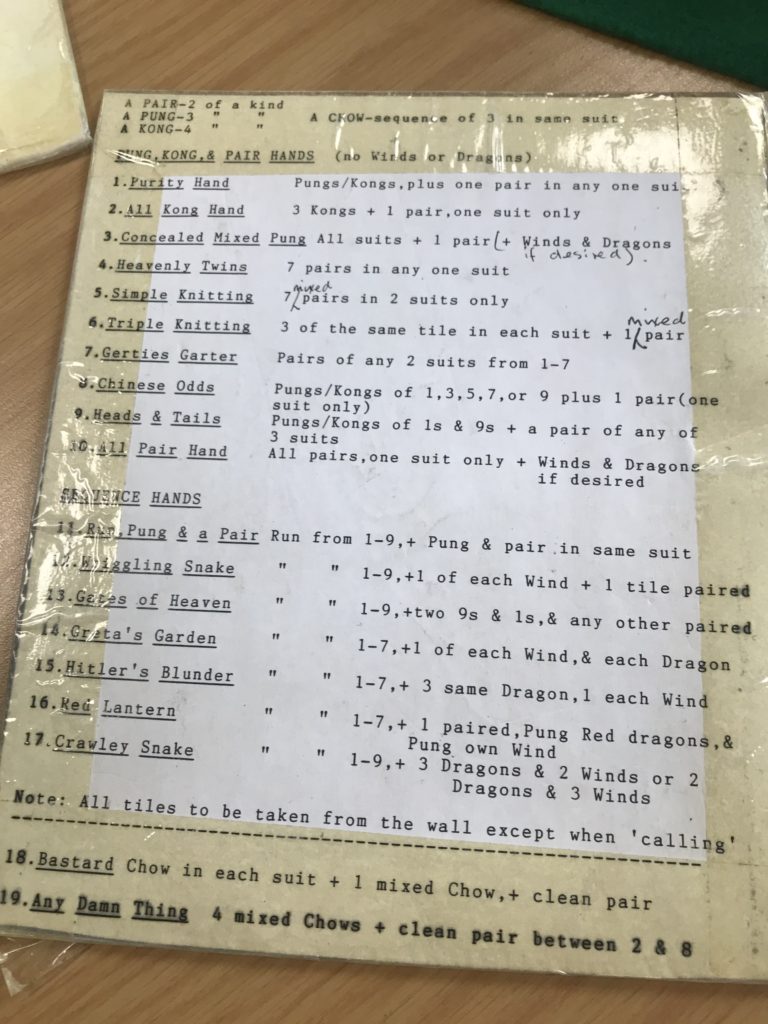

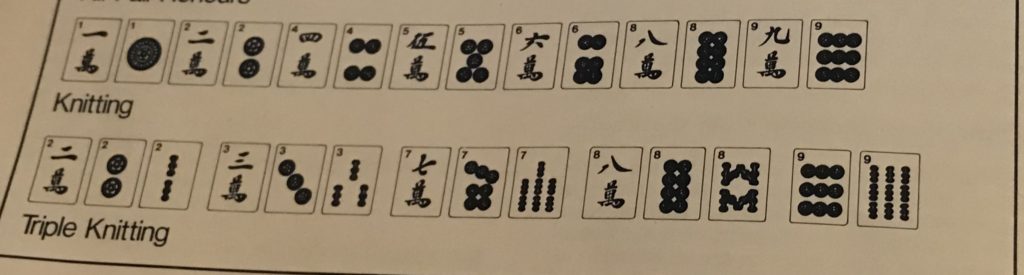

The “yaku” are actually less easy to remember than riichi, but one thing they have ahead of us are the names. Names like “Hitler’s Blunder” prove that however much the British try not to mention the war, we can’t help ourselves. They are also significantly more complex than those of riichi. Learning them is proving a tougher task even than when learning MCR’s notorious long list of scoring elements. British mahjong’s yaku don’t seem to have a common theme and moving between them during a game is harder. You really do have to choose one and go straight for it.

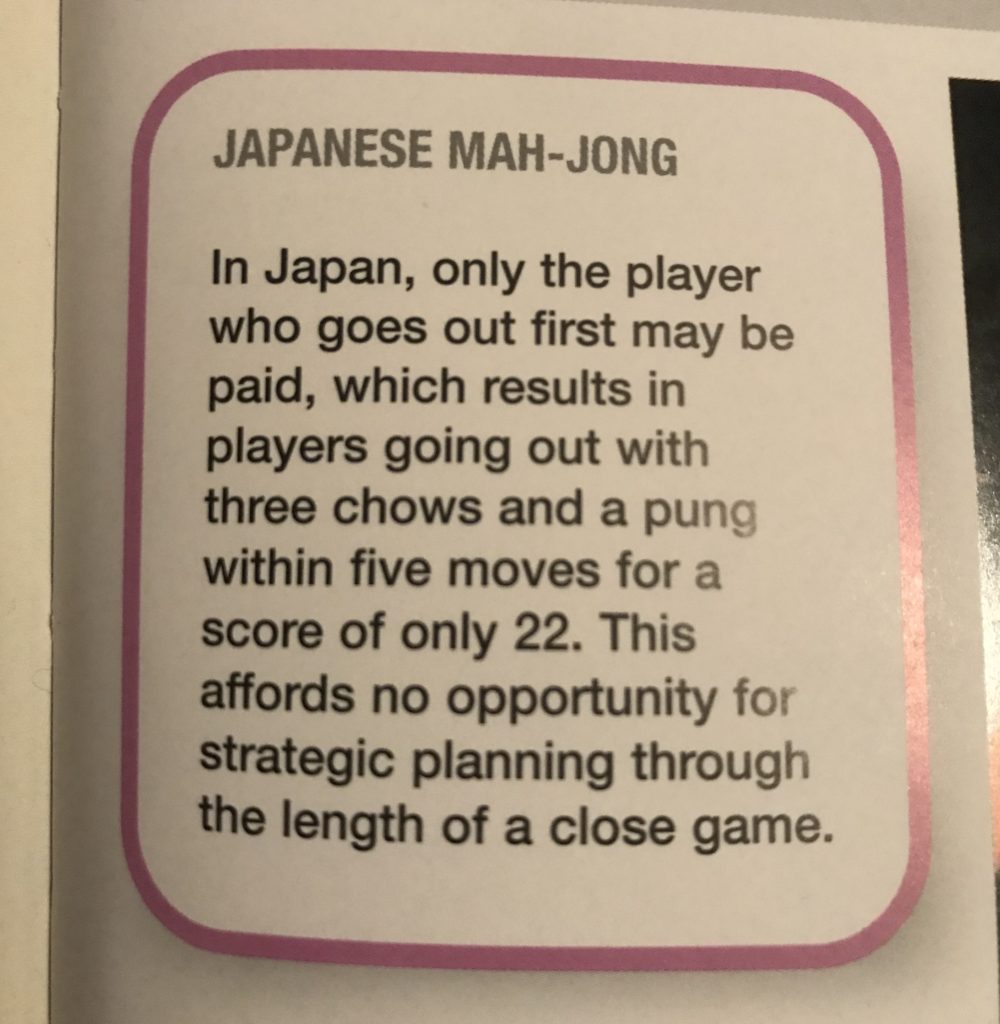

What do they think of riichi? They’re aware of the Japanese ruleset but they’re as nonplussed by our rules as we are by theirs. British has a similar rule to riichi in that you must declare yourself tempai or “fishing.” However, reading through their book reveals some misconceptions.

I’ll leave you kids to rage about the “no strategic planning” line. I don’t think I can add any more expletives that you can’t imagine yourselves.

Would I keep playing British mahjong? The answer is, yes. Curiously, for the same reason I keep playing riichi—I like the people.